Over the past 50 years, explained SC&I Professor of Journalism and Media Studies Regina Marchi, the two-day celebration of El Día de los Muertos (“The Day of the Dead”), observed on November 1 and 2 in Mexico and other parts of Latin America by decorating gravesites and/or creating altars in memory of deceased loved ones, has become very popular in the U.S.

For the last 25 years, Marchi, whose scholarship focuses on the intersections of media, culture, and politics, has researched how Day of the Dead has evolved from a rural, family-centered, religious tradition that was historically observed by indigenous agrarian peoples of Latin America, into an urban, public, secular, and political media phenomenon observed in the U.S. and other countries with sizeable Mexican populations.

Marchi is the author of Day of the Dead in the USA: The Migration and Transformation of a Cultural Phenomenon” (Rutgers University Press 2009; 2022), which won the 2023 International Latino Book Award for best political/current affairs book and the James W. Carey Award for Media Research, given by the Carl Couch Center for Social and Internet Research.

Marchi is the author of Day of the Dead in the USA: The Migration and Transformation of a Cultural Phenomenon” (Rutgers University Press 2009; 2022), which won the 2023 International Latino Book Award for best political/current affairs book and the James W. Carey Award for Media Research, given by the Carl Couch Center for Social and Internet Research.

SC&I spoke with Dr. Marchi to learn about similarities between Halloween and Day of the Dead, the contemporary presence of ancient symbols associated with the holiday, how Day of the Dead celebrations are a communication phenomenon, and lessons she strives to teach her students.

What are some of the major differences between Halloween and the Day of the Dead?

RM: These are two separate celebrations with separate histories, taking place in very different parts of the world. However, they have some similarities. Similar to Indigenous peoples of the Americas, pre-Christian Europeans believed it was crucial to honor family ancestors in order to ensure agricultural fertility and human reproduction. This is seen in the ancient three-day Celtic harvest celebration of Samhain, which took place in pre-Christian times in what is now Ireland, Scotland, Wales, the British Isles, parts of France and areas of Iberia (Spain and Portugal).

Since Nov. 1 was the first day of the Celtic new year, marking the end of the harvest season and the beginning of winter, it was thought to be a transitional time when the gates that separated the worlds of the living and the dead were open, allowing ghosts to roam the earth. Winter ushered in cold weather, darkness, and the “death” of most vegetation. During Samhain, household doors were left unlocked, fires were kept burning in the hearth all night, and offerings of food and drink were arranged on tables and doorsteps for the spirits of the dead who were believed to visit the living on this date.

This is very similar to the Day of the Dead practices of Indigenous peoples in Mexico and other areas of Latin America. Like ancient Celts, Indigenous agrarian populations historically believed that offerings must be made to the ancestors to ensure their blessings. Both ancient Celts and contemporary Indigenous peoples share the belief that spirits could partake of offerings of food and drink when they visited the earth. Celtic peoples lit bonfires and carved gourds with candles in them, which served as lanterns to scare away evil spirits. Similar practices still take place in rural areas of countries such as Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador.

This is very similar to the Day of the Dead practices of Indigenous peoples in Mexico and other areas of Latin America. Like ancient Celts, Indigenous agrarian populations historically believed that offerings must be made to the ancestors to ensure their blessings. Both ancient Celts and contemporary Indigenous peoples share the belief that spirits could partake of offerings of food and drink when they visited the earth. Celtic peoples lit bonfires and carved gourds with candles in them, which served as lanterns to scare away evil spirits. Similar practices still take place in rural areas of countries such as Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador.

To facilitate the conversion of Europe’s pagans to Christianity, the Catholic Church selected the pre-existing holy date of Samhain for the celebration of All Souls’ Day (Nov. 1) and All Saints’ Day (Nov 2) – a period in the Roman Catholic liturgical calendar for praying for the souls of the departed. This became known as “Hallowed Eve” or “Hallow’een,” and traditions of carving gourds and pumpkins to place as lanterns on doorsteps and in windows continued as secular practices, along with “souling” traditions of going door to door to ask for fruits, sweets or money. These traditions arrived in the United States in the mid 1800s via Irish, Scottish, and Welch immigrants, and evolved over time into our modern-day Halloween trick or treating. The celebration still has an emphasis on ghosts, skeletons, and pumpkins, but most Halloween celebrants no longer believe that spirits visit us at this time of year.

Similarly, when Catholicism was imposed upon the indigenous peoples of the Americas, their longstanding rituals of creating harvest altars or ofrendas (“offerings”) to honor deceased ancestors were forcibly moved to the dates of Nov. 1 and Nov 2 to become part of Catholic All Souls’ Day and All Saints’ Day traditions. At the root of Day of the Dead is a profound reverence and love that people express for their ancestors, and the belief that deceased family members visit their earthly relatives at this time of year.

So, in their origins, both Day of the Dead and Halloween share a belief that the spirits of the dead return to earth to visit around the time of November 1. Both celebrations involve pre-Christian traditions that had Christianity superimposed on them. The difference is that contemporary Day of the Dead celebrations still involve a very conscious remembering of departed loved ones, whereas most contemporary Halloween celebrations do not.

Are there ancient symbols associated with the Day of the Dead and, if so, what do they mean?

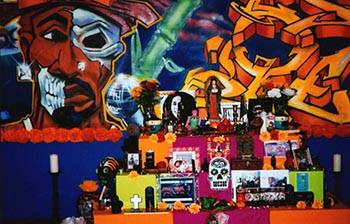

RM: There are quite a few ancient symbols associated with Day of the Dead that continue to be important today. Contemporary Day of the Dead altars are laden with offerings of food, beverages, incense, flowers, candles and mementos of the deceased. In particular, the marigold flower is prominent on Day of the Dead altars. This flower has been used in Mesoamerica to honor the dead since pre-Columbian times. Copal incense, which is made from pine resin, is also a pre-Columbian element that is commonly seen on Day of the Dead altars today, along with candles, grains, fruits, tubers, legumes, corn and other products of the harvest, symbolizing the origins of these altars as pre-Christian harvest festivals that honored the dead. Also seen on today's altars are items such as salt, cacao seeds, shells, and other items that were used as forms of currency in pre-Christian times. These would be placed on the altar as offerings for the dead. Water was often placed on altars to quench the thirst of traveling spirits and is still done today.

For many indigenous agricultural peoples of the Americas, the importance of the harvest in commemorating the dead illustrates a philosophical worldview in which the living and the dead are intrinsically connected in relationships of reciprocity. Death is not considered the “end” of life, but rather, the continuum of life, necessary for regeneration and rebirth. The symbolic association of life (harvest, fertility, sexuality, birth) and death is visible in past and present rituals for honoring the dead in both Europe and Latin America.

Do you teach your Journalism and Media Studies students about the Day of the Dead?

RM: I have taught a Byrne Seminar about Day of the Dead, and in my undergraduate classes Gender, Race and Class in the Media or Media and Social Change, as well as my doctoral seminar on Media and Culture, I teach about Day of the Dead celebrations in the United States, which grew out of the Chicano Movement for Civil Rights. In a U.S. society that had long segregated, devalued and exploited Latinos, ignoring their histories and contributions, Chicanos (a self-identifying term used by  Mexican Americans involved in or supportive of progressive political organizing work), adopted and publicly celebrated Dia de los Muertos starting in the early 1970s. At that time, the celebration was unknown to most people the US, including most Mexican Americans. Its birth here in the US was a political statement that validated Indigenous Mexican cultures (largely disdained in Mexico at that time) and recognized the influence of indigenous worldviews on contemporary US Mexican American communities. In the US context, public Day of the Dead altars became communication media that raised awareness concerning Mexican and larger Latino identities, histories and collective experiences. As political expressions that publicly celebrated deceased Latino cultural icons, many of these altars also honored groups of people who were victims of preventable causes of death, such as war, violence against women, violence against LGBT populations, gun violence, police brutality against people of color, the death of the environment, and other sociopolitical issues.

Mexican Americans involved in or supportive of progressive political organizing work), adopted and publicly celebrated Dia de los Muertos starting in the early 1970s. At that time, the celebration was unknown to most people the US, including most Mexican Americans. Its birth here in the US was a political statement that validated Indigenous Mexican cultures (largely disdained in Mexico at that time) and recognized the influence of indigenous worldviews on contemporary US Mexican American communities. In the US context, public Day of the Dead altars became communication media that raised awareness concerning Mexican and larger Latino identities, histories and collective experiences. As political expressions that publicly celebrated deceased Latino cultural icons, many of these altars also honored groups of people who were victims of preventable causes of death, such as war, violence against women, violence against LGBT populations, gun violence, police brutality against people of color, the death of the environment, and other sociopolitical issues.

What lessons from the Day of the Dead celebrations do you most hope to communicate to your students and why?

RM: I’d like students to recognize the universality of Day of the Dead. Traditions of altar making to honor the deceased occur in cultures around the world, which is why people from diverse countries, races and ethnicities are drawn to Day of the Dead. I also want students to understand the relationship between culture and politics. Cultural traditions are not apolitical. All cultural traditions involve power dynamics and complex processes of destruction and innovation. Day of the Dead is an example of the communicative capacity of public cultural rituals in identity construction, community building, education, and political protest.

Learn more about the Journalism and Media Studies major on the Rutgers School of Communication and Information website.

Photos: Courtesy of Regina Marchi. Captions, top to bottom: Day of the Dead altar; Cover of Marchi's book; altar for victims of gang violence; Day of the Dead altar; altar remembering human rights activists.